As part of a transparency report by eSafety, the commission sent “legally enforceable periodic transparency notices” to Apple, Discord, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Skype, Snap, and WhatsApp to find out how they detect and prevent child exploitation.

While Skype is no longer active, the report found that in the other platforms, there were critical gaps that created risks of child exploitation and abuse.

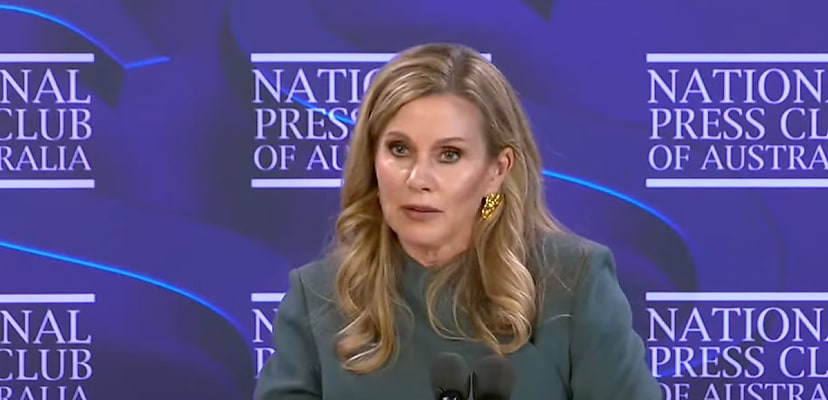

“It’s disappointing to not see bigger steps taken by these powerful companies to tackle child sexual exploitation and abuse being perpetuated at scale on their platforms and services,” said eSafety commissioner Julie Inman-Grant.

“These companies have the resources and technical capability to make their services safer, not just [for] children but for all users. We’ve engaged with these companies about these issues for the past decade and highlighted these safety shortcomings in our previous transparency reports.”

According to the results, the platforms had inadequate proactive detection of child sexual exploitation within video calls, insufficient detection of newly created child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and limited application of language analysis systems to detect cases of sexual extortion.

“The Australian public rightly has an expectation that tech companies should be doing all they can, including to innovate new technologies and embed safety by design, to protect children,” Inman-Grant said.

“This is not just a question of legality, it’s a critical matter of corporate conscience and accountability. Without significant uplift in available safety technologies and practices, we’ll continue to see devastating consequences for children and young people.

“This is not just how platforms are being colonised by organised criminals to target young Australians with sexual extortion but also the enabling and perpetuating of incredibly damaging online and personal harms.”

The eSafety Commissioner addressed the issue in the context of the social media ban, which prohibits people under 16 years of age from using social media platforms.

“And people ask why governments are moving to bans rather than pushing them to make their platforms safer? If companies are not sufficiently motivated to tackle these egregious and illegal harms, what prospects for online safety do our children really have in the digital world today?” Inman-Grant said.

However, the report found that there were a number of improvements the platforms had made since the first transparency report, including increased response times to reports of sexual abuse, better industry information sharing, expansion of systems that blur sexually explicit videos and images and the expansion of detection tools for already identified CSAM and other abusive material.

“It’s incumbent upon the tech industry to work together to develop new technologies to detect online harm,” she said.

“I call on industry to address these safety gaps and take steps to stop harmful child sexual exploitation and abuse material and activity from taking place on their services.

“They have the capability – we need to see much greater will translated into meaningful protections.”

The tech giants will be required to report to eSafety again in March and August 2026, with the commission to publish reports based on the responses.

UNICEF backs eSafety

Responding to the commissioner on LinkedIn, UNICEF Australia said protecting children is at the core of its mission and that appropriate online safety practices are required for that.

“Many tech companies have the tools to better protect children online, but what we currently have is a patchwork of effort. Instead, what we need is consistency. UNICEF knows from our work around the world that people who intend to harm children will exploit inconsistency wherever they find it,” said UNICEF Australia’s head of digital policy, John Livingston.

The charity also highlighted the new risks presented by AI and said that “we have a critical opportunity to lead in making Australia the safest place in the world for children to go online”.

Daniel Croft